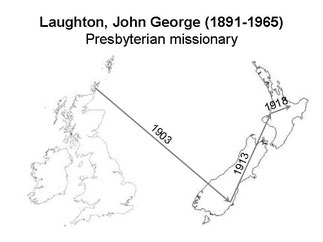

John George Laughton was born in Holm parish, Orkney, Scotland, in 1891. He was the son of John Laughton, a farmer, and his wife, Mary Ann Balfour Moody Shearer. He emigrated to New Zealand with his parents in 1903, and grew up in Mosgiel (south of Dunedin). He attended the University of Otago and Knox College in Dunedin. In 1913 he was appointed student minister to Piopio in the King Country (North Island) and in 1914 was ordained as a home missionary there. On 23 December 1915 at Piopio he married Margaret Leask, who died in 1917.

In 1916 he began working with Maori people. Laughton's ministry at Piopio covered vast back-country areas. He identified closely with Maori, becoming adept at their language and earning their respect and affection; they called him 'Hoani'. He developed an intimate knowledge of all that concerns the Maori people, and was highly esteemed and loved by both Maori and pakeha.

In 1918 he was invited to join the Presbyterian Maori mission, and he moved to Maungapohatu in the Urewera, with Sister Annie to help him. Maungapohatu was his base for eight years. His father joined him there, and in 1921 Laughton was ordained as a full minister in the Presbyterian church and as a missionary to Maoris. In 1921 he married Horiana Te Kauru of Nuhaka (1899 – 1986), a graduate of Turakina Maori Girls' School and a member of the Maori Missionary staff. They were to have five children.

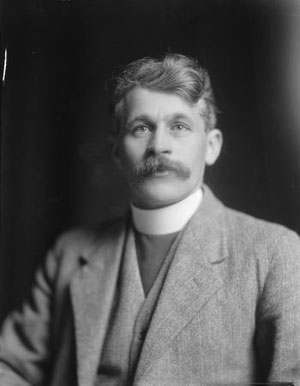

The prophet Rua Kenana had founded his religious community at Maungapohatu. Rua was released from prison in April 1918 and from the beginning Rua’s relationship with Laughton was marked by deep theological tensions. Rua claimed to be Jesus Christ's brother and the Messiah, which Laughton found unacceptable. However, through tact and careful listening on Laughton's part, and open interest on Rua's, they developed mutual trust and friendship. They worked out a concept of unity based on the belief that one God could be found through different pathways. This brought together followers of the Ringatu, Iharaira and Presbyterian faiths. Through his association with Rua and the people of Maungapohatu, Laughton gained an intimate understanding of Maori thought and tradition. Tuhoe conferred rangatira status on him, and Laughton conducted Rua's funeral service in 1937.

Laughton and Rua shared a commitment to Maori education and founded a school at Maungapohatu in 1918. In the same year Laughton and the Reverend H. J. Fletcher went to Ruatahuna and built a school there. Later Laughton established schools at Matahi (1921), Tanatana (1922) and Te Teko (1926).

Laughton worked with the missionary Mrs Gorrie, who moved to Onepu in 1919, where she began teaching at the local marae. She founded the Maori Mission School there. More than 150 children, spanning two generations of the Ngati Tuwharetoa iwi, received an education from the Presbyterian Church until the school in Onepu closed in 1959.

In 1926 Laughton was transferred to Taupo. For the next 12 years this was the base for his richly diverse, visionary and expanding ministry. He trained young Maori men for the ministry, became mentor to new recruits to the mission (lay and ordained, Maori and Pakeha), and spearheaded new developments in education. Totally committed to a renaissance of the Maori language, Laughton founded a press, Te Waka Karaitiana. This published the journal Te Waka Karaitiana, which he edited. Selections from the ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ appeared in Te Waka and were bound in a book. He compiled and personally sponsored the publication of the Presbyterian Maori service book. He also published Maori translations of portions of Scripture, Te Katikihama Poto (the Shorter Catechism), and general news of the Christian churches.

In 1936 Laughton was appointed superintendent of the Presbyterian Maori missions. He established a Maori boys' training farm (Te Whaiti) and five urban boarding hostels for young Maori men and women. Local Maori parishes were growing vigorously, and Laughton encouraged them to become more autonomous. He set up special Maori structures for church administration and ministry training.

In 1945 the Presbyterian church created the Maori synod (Te Hinota Maori) as a separate entity. Laughton's vision of a marae base for the mission culminated in the official opening of Te Maungarongo meeting house at Ohope, in 1947. When Te Hinota Maori was established as a full synod of the Presbyterian church in 1956, Laughton was elected inaugural moderator; he held this position until his retirement in 1962.

Laughton's achievements were recognised in many ways. In 1942 he became moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of New Zealand. In 1948 he was appointed a CMG for services to Maori and the Maori church. In 1950 he supervised the printing of the revised Maori Bible after four years organising the project. He was a justice of the peace. He was also a member of the Polynesian Society.

He moved to Ohope in 1938, and to Whakatane in 1956. In 1962 he retired from full time work to work part time. He died in Rotorua in 1965, and was survived by his wife, two daughters and two sons. He was buried at Hillcrest cemetery, Whakatane.

John Laughton was a humble, gentle man with a deep love of Maori and the Christian faith. These attributes formed the foundation of a ministry that crossed all denominational and tribal boundaries. The people of Maungapohatu delivered a stone from their sacred mountain to rest on his grave.

Largely drawn from http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4l4/1

and http://www.archives.presbyterian.org.nz/Page176.htm

Laughton’s involvement in translating Te Paipera Tapu and his legacy

John Laughton was chairman of the team that translated the Maori Bible (the fourth edition), which was published in 1952. Although this version of Te Paipera Tapu is a taonga, for some, particularly those for whom Maori is a second language, the language is now dated.

In 2009 the Bible Society New Zealand began a new translation of the Bible in Maori. This was the largest translation task undertaken by the Bible Society in New Zealand since 1952. The text was unchanged, but the translation was made more readable. Changes included macrons to indicate long vowels, modern punctuation including speech marks and paragraphs, book introductions, section headings and maps. The complete enhanced Maori Bible was published in 2012.

THE MAORI BIBLE

BY THE VERY REV. J. G. LAUGHTON

The story of the Maori Bible is interesting in more ways than one. Of course, it appeals to the religious community; but it also has something for scholars of language and literature. In a way, the reduction of the Maori language to a written form parallels with the work of the early translators of Holy Writ into the English tongue, and in a way again it leads from their efforts.

Of course, it is not true that the work of the European grammarians and linguists has developed the Maori language to its present capacity as a vehicle for human thought. The Maori language had evolved to that standard before the first white man ever sighted these shores. The language abounded with poetry of rare beauty, and through the common speech ran metaphors and similes and pictures of the mind. The aristocratic and priestly class of the whare-wananga, the sacred school of learning, had developed religious concepts in the Maori tongue which were deeply abstract, and in many ways these concepts resembled those of the Hebrews in whose speech two-thirds of the Scriptures were first transcribed. The Maori language was fully capable of formulating and expressing these ideas. The language, melodious but unknown, which fell upon the ears of Marsden and his men when they first set foot in New Zealand was a full-grown oracle of legend and poetry, genealogy and religious concept. But at this stage it was only a spoken language.

We can imagine the search for the first few words which would give access to even the outer lobby of the language house of a people's mind. The credit for taking that first bridgehead in the wide territory of the Maori language belongs to Thomas Kendall, one of Marsden's earliest band of missionaries. Kendall had been a London schoolmaster, and he is credited with doing the first great service of reducing the Maori language to a written form. Kendall's book was printed in Sydney in 1815, and was a great help to Professor Samuel Lee in compiling the first Maori grammar and vocabulary.

EARLY PRINTINGS OF THE SCRIPTURES

Kendall's book was the bridgehead, and the missionaries then began the immense task of translation. The first Scriptures in Maori came from the press in Sydney in August, 1827. These were six chapters—four from the Old Testament and two from the New, with the Lord's Prayer and seven hymns. In July, 1830, in Sydney, a further book was printed containing other short extracts from the Old and New Testaments, some prayers, a catechism and some nineteen hymns.

In 1833 William Yate, of the Church Missionary Society, superintended the printing in Sydney of 1, 800 copies of the first and fourth Gospels, the Acts, the Epistle to the Romans, the First Epistle to the Corinthians, and eight chapters of Genesis.

The year 1835 was a milestone in the history of the Maori Scriptures, for in that year a printing press was landed at Paihia, and William Colenso undertook the printing.

Colenso speaks of some of his difficulties. When the packages were brought ashore it was found that some essential equipment had not been included. This had to be improvised out of local wood and stone. Most serious of all, by a curious oversight, no paper had been sent with the press. The wives of the missionaries came to the rescue and brought forward their own supplies of writing paper, sufficient to produce immediately 2.000 copies of the Epistles to the Ephesians and the Philippians. They were the first books to be published in New Zealand.

A complete edition of the New Testament was issued at Paihia by the Church Mission in 1837. This had engaged the attention of the entire Mission community during the preceding seven years.

The translation of the New Testament was chiefly due to the remarkable linguistic capacity of William Williams. Later Robert Maunsell did similar service in assisting to complete the Old Testament. When we remember that these first translations were made from the Greek and Hebrew into Maori which today stands so high in idiomatic purity, we recognise the industry and profound scholarship which enabled these early translators to bring it to such perfection.

WILLIAMS, MAUNSELL, HOBBS

Each and every one of the missionaries had a part in the work of translation, but special honour must be given to William Williams and Dr. Maunsell, of the Church of England, and to John Hobbs, Thomas Buddle and Alexander Reid, of the Wesleyan Mission. From 1836, the Press of the Wesleyan Mission printed Hobbs's translation of the book of Job and an edition of 6, 000 copies of “Translations from the Old Testament.” Hobbs was a master of idiomatic Maori.

The Rev. Robert Maunsell set to work translating the Old Testament within a year of his arrival at the Bay of Islands. Many stories are told of the pains Maunsell took to perfect himself in the use of Maori words. He would slip quietly into a pa and sit listening to conversations. Later he offered small rewards to any Maori who could prove him wrong in his use of Maori words.

Disaster overtook this tireless worker. Twice within a fortnight in 1843 his quarters on the lonely mission station to which he had moved were destroyed by fire, and his precious translations were destroyed. Many men would have thrown up the task in despair. After a few weeks this great man began his work all over again.

The Old Testament, chiefly the work of Mr. Maunsell, was first issued in three separate volumes; but in 1856 a Board of Revision set to work, and three years later prepared for an issue of the whole Bible in one volume. But it wasn't until 1862 that a fully revised copy was sent to London, and only in 1868 that the first Maori Bible in a single volume left the press.

The second edition of the complete Bible was the result of a revision of the text by Archdeacon Maunsell and Archdeacon W. L. Williams. This was issued in 1887, and remained the standard version until 1924, when a further revision by Bishop Herbert Williams was completed and published. This third complete Maori Bible is now out of print and a still further revision is being prepared. The 1924 edition, which was a standard of Maori diction, was unfortunately marred by many typographical errors.

The present revision is being carried out under the supervision of the British and Foreign Bible Society. For revising, the Bible was divided into sections and thoroughly proof-read twice over by a panel of ten outstanding Maori scholars. In March, 1946, a conference of representative scholars met to review their corrections and to determine the question of proposed amendments and the general format of the new volume.

The reports of the proof readers raised the question of whether something far more extensive than a mere correction of typographical errors was not called for. It was the first time that a body of scholars from the Maori race itself had been engaged in a careful review of the text of the Maori Scriptures. From them chiefly came the suggestions for clearing up obscure passages. Then there were numerous passages in which the translation, while correct, could be immensely improved to Maori ears by giving it a more characteristically Maori turn of idiom. The members of the conference also felt that the alternative reading of the English revised version should be followed as a basis for the revised translation in many passages. Fully realising how great an undertaking it was applying itself to, the conference decided that a full revision of the whole Maori Bible should be made before the next publication, and appointed a Revision Committee.

INTEREST OF MAORI PEOPLE

In the intervening months members of the committee have worked steadily at the task of revision. Various portions of the text have been assigned to the different members who have prepared revised scripts, and these in turn submitted to the full committee at the five sessions which have been held since March, 1946. The revision of the New Testament has been completed, and at the session which has just ended in Wellington the committee has been engaged on the revision of the books of Genesis and Psalms in the Old Testament.

Perhaps the most encouraging feature of this whole movement to revise the Maori Bible is the deep interest which the Maori people everywhere have taken in it. Not only are they subscribing funds. They are keenly interested in the work which the committee is doing. No edition of the Maori Bible since the first has been looked forward to with such eagerness as the one at present being prepared. Maori minds and money and devotion are being given to it. In a new sense it will be the Maori Bible. Some of the funds subscribed have come from groups of Sunday schools, and public school children.

These tokens hearten the committee in work which often calls for long and concentrated research into the meaning of a single word, or the right turn of a single phrase. The members of the committee are working for the generation which these children represent. The new Maori Bible, which is the product of over a century of scholarship, will bring them, and the generations after them, the Holy Scriptures in their mother tongue.

Journal of the Polynesian Society, 1947, Volume 56, No. 3, pp 290 – 294

This article was broadcast by the National network of stations on 3 August, 1947

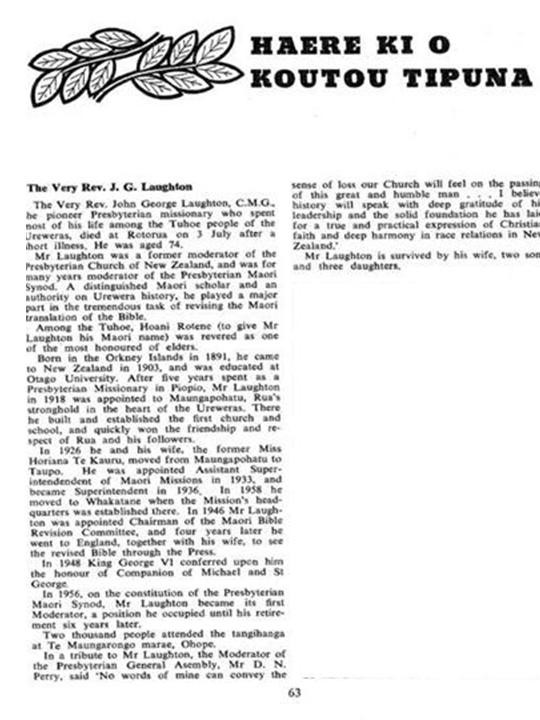

John Laughton’s obituary in Te Ao Hou (The Maori Magazine), issue 52 (September 1965):

Hazelnut Herald (from Aotearoa)

www.hazelthenut.jimdo.com

Hazelnut Herald (from Aotearoa)

www.hazelthenut.jimdo.com